Manuscript proposals: [email protected] / 0745 204 115 //// Tracking orders Individuals / Sales: 0745 200 357 / Orders Legal entities: 0721 722 783

Publisher: Cișmigiu Books

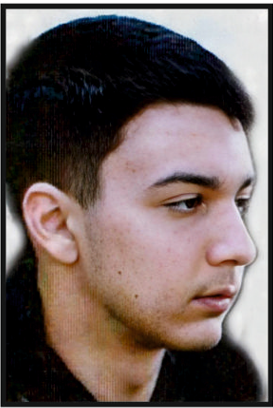

Author: Andrei Matei Popescu

Edition: I

Pages: 110

Publisher year: 2024

ISBN: 978-606-28-1895-1

Product Code:

9786062818951

Do you need help?

0745 200 357

- Description

- Download (1)

- Authors

- Content

- More details

- Reviews (0)

The bar code of forgotten memories, stored in the "single age of life", childhood, is a symbol for deciphering the white contour line on a black page.

The mirror through which the face overflows and turns into a black outline on a white page is a form of writing. White and black in an equal color give way to one another, in the only possibility of communication of a lost love, and thus melancholy becomes creative.

The fragility of the human being in the permanent struggle with masks, perfectly tight on the face and soul, is related to personal fragility in a society that wants you to be its slave.

The book "Happy sad" by Andrei Matei Popescu is unique in its personal style of confession and communication, simplified to the cry "Here's the Man!".

Clelia Ifrim

The mirror through which the face overflows and turns into a black outline on a white page is a form of writing. White and black in an equal color give way to one another, in the only possibility of communication of a lost love, and thus melancholy becomes creative.

The fragility of the human being in the permanent struggle with masks, perfectly tight on the face and soul, is related to personal fragility in a society that wants you to be its slave.

The book "Happy sad" by Andrei Matei Popescu is unique in its personal style of confession and communication, simplified to the cry "Here's the Man!".

Clelia Ifrim

-

Happy sad

Download

ANDREI MATEI POPESCU

Born on May 2, 2007, Târgu Jiu, he attended "Alexandru Ștefulescu" Secondary School, continuing his studies at Energetic High School. After the 9th grade, he transferred to the "Spiru Haret" National College in the locality.

At the age of 16, Andrei was a very sensitive teenager, feeling emotions deeply, describing himself as "joyful and sad". Intelligent and talented, he was attracted to the artistic side, music and literature, which he expressed through his own compositions (hip-hop music), writing (essays, poetry). His talent stood out through song, recitation of poems and through the interpretation of the main role of the play "Mahmur" written by himself, being repeatedly awarded at competitions within the school.

As personalities, he was fascinated by the writings of Charles Bukowski, Radu Gyr, Franz Kafka. Passionate about deep ideas and concepts, philosophy gave him a broader understanding of the world.

Andrei will remain in the memory of those who knew him and who were always by his side.

"Maturation" means the end of hope, as he left in his writings.

Foreword / 5

Ecce homo! / 11

Happy sad / 15

I am you – null / 26

Tell them I'm crazy / 32

Tell them I'm crazy / 38

Poem 1 – Slide / 49

Poem 2 – Dear mother / 52

Poem 3 – End of an Era / 54

Poem 4 – Rest in peace, Horia! / 56

Poem 5 – Meteahna / 58

Poem 6 – Run / 59

Hangover / 60

Tell them I'm crazy / 75

Dehumanization of the inevitable / 88

My dream is a prophecy / 97

Afterword / 107

Ecce homo! / 11

Happy sad / 15

I am you – null / 26

Tell them I'm crazy / 32

Tell them I'm crazy / 38

Poem 1 – Slide / 49

Poem 2 – Dear mother / 52

Poem 3 – End of an Era / 54

Poem 4 – Rest in peace, Horia! / 56

Poem 5 – Meteahna / 58

Poem 6 – Run / 59

Hangover / 60

Tell them I'm crazy / 75

Dehumanization of the inevitable / 88

My dream is a prophecy / 97

Afterword / 107

It was given to me in this life to live among young people and among books...

A privileged destiny, up to a point, I could say... Up to that point when life shows you that sometimes the two dimensions of a man's soul, the human and the bookish, intertwine in such a way that they almost get confused. ..

Two years ago I knew Andrei Popescu, a creative young man, always inspired, with a somewhat contradictory psychological fabric.

His being gave me back the certainty that, as the philosopher Gabriel Liiceanu said, man is placed in a wrong relationship with time and with the way we relate to our own freedom. Man is, paradoxically, a free being, chained in time...

For Andrei, the chain of time was overcome by his own freedom... He chose not to submit to it, the ruthlessness of time, and he overcame it by his own choice, leaving behind his word, spoken or written.

Now, when I look back and reread his words on paper in the lines of this book, sometimes chaotic (for the lonely thought of man is uncontrollable), I think about how his being swayed between several experiences...

Writing is not an unmodulated scream... It requires vigor, construction and drama to be able to express yourself as deeply as Andrei did.

His affective self had devoured the state of loneliness, his being had simply tumbled between dichotomies: between being and not being saved, as he himself admits in the first lines of the book, between dreams and nightmares, between delight and nothingness, between angelic and demonic, between joy and sadness, between peace and chaos, between forgetting and not forgetting, between simple and complicated, black and white, bad luck and luck, light and dark, experiences oxymorons that led him to the dance of letters...

Reading his creation, I thought of the experience of the baby quail from the story of Ioan Alexandru Brătescu-Voinești, as a symbol of supreme desolation, ready at any time to emerge from the very essence of life, at the distances that, with age, we put between ourselves and others, so that every drama of the world does not automatically become ours, at the door of the soul opened with measure, so that no more misery enters us than we can leads to the necessary degree of insensitivity adjusted every day to be able to get through life...

I think that Andrei had built a shell of his soul, and his protective layers were literature, music and solitude, the necessary return to himself.

Probably this cruelty of life and his own self, sometimes disguised in moralizing stories, written or sung by him on the stages of our city, the idea that vulnerability is the very essence of the human condition bore fruit in his soul and determined his thoughts, extremely deep ...

Most of the time, the emotional life in a family flows through underground beds, and the waters springing from everyone's soul meet each other silently. And silence was a generator of creativity for Andrei Popescu....

Could the author, sometimes slightly daring, impudent and revolting at his own self, sometimes a repetitive talker, bet on the idea that, opening the rooms of his soul, the world begins to enter? And the world enters, for the intimate arouses curiosity, and this child's book does directly what literature usually does through a series of masks. At some point the book tends to become pure philosophy, but literature seems to succeed where philosophy fails. Therefore, nothing remains outside it, nothing is foreign to it. Neither the inner voices that took over his being, nor the idea that in this life there is a need for repentance, deliverance, solitude, love, a cry...

It is certain that we disappear for a while regretted by a few who loved us, we are indifferent to most of those around us... Anyway, the speed with which we are evacuated from this world, once we have left it, is enormous...

When the last man who loved us also disappears, we become... WORD!

This seems to be the idea that Andrei leaves us through the lines of this book that disturbs, excites, scares, overwhelms the being!

Perhaps, if I had ever asked him how he felt when he wrote it, he would have told me: cheerfully sad, teacher, cheerfully sad...

And maybe, if I had asked him what he wanted to express through his self-confession, he would have answered that he made a pilgrimage of forgiveness to his own self, or maybe he would have answered me like Marin Sorescu once did about the soliloquy of the biblical Jonah: I can't answer you anything (...). Everything gets confused in my memory. I only know that I wanted to write something about a lonely man, incredibly lonely..."

Personally, writing these lines, thinking about this "beautiful and wonderful and wretched and wretched hell of years" that we all live, I think of what the American writer Robert A. Heinlein said: The supreme irony of life is that no one gets out of it alive...

P.S.

We miss being able to

to be no more

miss you...,

our dear Andrei!

Professor Gheorghita Clipicioiu

A privileged destiny, up to a point, I could say... Up to that point when life shows you that sometimes the two dimensions of a man's soul, the human and the bookish, intertwine in such a way that they almost get confused. ..

Two years ago I knew Andrei Popescu, a creative young man, always inspired, with a somewhat contradictory psychological fabric.

His being gave me back the certainty that, as the philosopher Gabriel Liiceanu said, man is placed in a wrong relationship with time and with the way we relate to our own freedom. Man is, paradoxically, a free being, chained in time...

For Andrei, the chain of time was overcome by his own freedom... He chose not to submit to it, the ruthlessness of time, and he overcame it by his own choice, leaving behind his word, spoken or written.

Now, when I look back and reread his words on paper in the lines of this book, sometimes chaotic (for the lonely thought of man is uncontrollable), I think about how his being swayed between several experiences...

Writing is not an unmodulated scream... It requires vigor, construction and drama to be able to express yourself as deeply as Andrei did.

His affective self had devoured the state of loneliness, his being had simply tumbled between dichotomies: between being and not being saved, as he himself admits in the first lines of the book, between dreams and nightmares, between delight and nothingness, between angelic and demonic, between joy and sadness, between peace and chaos, between forgetting and not forgetting, between simple and complicated, black and white, bad luck and luck, light and dark, experiences oxymorons that led him to the dance of letters...

Reading his creation, I thought of the experience of the baby quail from the story of Ioan Alexandru Brătescu-Voinești, as a symbol of supreme desolation, ready at any time to emerge from the very essence of life, at the distances that, with age, we put between ourselves and others, so that every drama of the world does not automatically become ours, at the door of the soul opened with measure, so that no more misery enters us than we can leads to the necessary degree of insensitivity adjusted every day to be able to get through life...

I think that Andrei had built a shell of his soul, and his protective layers were literature, music and solitude, the necessary return to himself.

Probably this cruelty of life and his own self, sometimes disguised in moralizing stories, written or sung by him on the stages of our city, the idea that vulnerability is the very essence of the human condition bore fruit in his soul and determined his thoughts, extremely deep ...

Most of the time, the emotional life in a family flows through underground beds, and the waters springing from everyone's soul meet each other silently. And silence was a generator of creativity for Andrei Popescu....

Could the author, sometimes slightly daring, impudent and revolting at his own self, sometimes a repetitive talker, bet on the idea that, opening the rooms of his soul, the world begins to enter? And the world enters, for the intimate arouses curiosity, and this child's book does directly what literature usually does through a series of masks. At some point the book tends to become pure philosophy, but literature seems to succeed where philosophy fails. Therefore, nothing remains outside it, nothing is foreign to it. Neither the inner voices that took over his being, nor the idea that in this life there is a need for repentance, deliverance, solitude, love, a cry...

It is certain that we disappear for a while regretted by a few who loved us, we are indifferent to most of those around us... Anyway, the speed with which we are evacuated from this world, once we have left it, is enormous...

When the last man who loved us also disappears, we become... WORD!

This seems to be the idea that Andrei leaves us through the lines of this book that disturbs, excites, scares, overwhelms the being!

Perhaps, if I had ever asked him how he felt when he wrote it, he would have told me: cheerfully sad, teacher, cheerfully sad...

And maybe, if I had asked him what he wanted to express through his self-confession, he would have answered that he made a pilgrimage of forgiveness to his own self, or maybe he would have answered me like Marin Sorescu once did about the soliloquy of the biblical Jonah: I can't answer you anything (...). Everything gets confused in my memory. I only know that I wanted to write something about a lonely man, incredibly lonely..."

Personally, writing these lines, thinking about this "beautiful and wonderful and wretched and wretched hell of years" that we all live, I think of what the American writer Robert A. Heinlein said: The supreme irony of life is that no one gets out of it alive...

P.S.

We miss being able to

to be no more

miss you...,

our dear Andrei!

Professor Gheorghita Clipicioiu

If you want to express your opinion about this product you can add a review.

write a review

![Happy sad [0] Happy sad [0]](https://gomagcdn.ro/domains/editurauniversitara.ro/files/product/medium/vesel-de-trist-260867.jpg)

![Happy sad [1] Happy sad [1]](https://gomagcdn.ro/domains/editurauniversitara.ro/files/product/medium/vesel-de-trist-775107.jpg)

![Happy sad [1] Happy sad [1]](https://gomagcdn.ro/domains/editurauniversitara.ro/files/product/large/vesel-de-trist-260867.jpg)

![Happy sad [2] Happy sad [2]](https://gomagcdn.ro/domains/editurauniversitara.ro/files/product/large/vesel-de-trist-775107.jpg)