Manuscript proposals: info@editurauniversitara.ro / 0745 204 115 //// Tracking orders Individuals / Sales:0745 200 718 / 0745 200 357 Orders Legal entities: 0721 722 783

ISBN: 978-606-28-1465-6

DOI: 10.5682/9786062814656

Publisher year: 2022

Edition: I

Pages: 348

Publisher: Editura Universitara

Author: Ilinca Stroe

Product Code:

9786062814656

Do you need help?

0745 200 718

/

0745 200 357

- Description

- Download (1)

- Authors

- Content

- More details

- Where to find it

- Reviews (0)

This thesis is as much my product as it is, in various ways, the creation of a number of people to whom I offer thanks and my gratitude.

I owe the historical orientation, no less than the diplomatic vision, and the first contact with Paul Carter’s work to Prof. Simon During and Dr. Ken Gelder, respectively. I am indebted to Dr. David Bennett for a few very useful suggestions, and to Dr. Irina Grigorescu-Pană for the first glimpse of Australian literature. For beneficial comments, advice and support, thanks to my fellow postgraduates Kelly Farrell, Amanda Claremont, Robert Beardwood, Ioana Petrescu, Michelle Borzi, Jonathan Carter and Blair Mahoney.

I am particularly grateful to Jude and Glen Walker, and to Mr. Quin for their exceptional kindness and for the homely atmosphere they created for me; to Bradley Crouch, Irina Dumitrescu, Lucy Edwards, Chris Foley, Allan Horsfall, Janine King, Tudor Stancu, and Dr. Gail Tulloch for their friendship, support, and good company. Above all, I thank my parents, my brother, Mihaela Rusu and Simona Combi for having constantly encouraged and counseled me from a distance.

Smaller, but still important aspects of my approach have been shaped by the merely coincidental impressions of “ordinary people”. I thank, therefore, Sra Dolores Molina González for reminding me that literature is a bit like Simón Bolívar’s eyes in a mirror; Edgardo García for remarking that Australia, like Britain, is an island; and the two Aboriginal women at the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre for the meaning of silence.

Last but not least, I am grateful to The University of Melbourne for offering me the opportunity to study in Australia.

Ilinca Stroe

I owe the historical orientation, no less than the diplomatic vision, and the first contact with Paul Carter’s work to Prof. Simon During and Dr. Ken Gelder, respectively. I am indebted to Dr. David Bennett for a few very useful suggestions, and to Dr. Irina Grigorescu-Pană for the first glimpse of Australian literature. For beneficial comments, advice and support, thanks to my fellow postgraduates Kelly Farrell, Amanda Claremont, Robert Beardwood, Ioana Petrescu, Michelle Borzi, Jonathan Carter and Blair Mahoney.

I am particularly grateful to Jude and Glen Walker, and to Mr. Quin for their exceptional kindness and for the homely atmosphere they created for me; to Bradley Crouch, Irina Dumitrescu, Lucy Edwards, Chris Foley, Allan Horsfall, Janine King, Tudor Stancu, and Dr. Gail Tulloch for their friendship, support, and good company. Above all, I thank my parents, my brother, Mihaela Rusu and Simona Combi for having constantly encouraged and counseled me from a distance.

Smaller, but still important aspects of my approach have been shaped by the merely coincidental impressions of “ordinary people”. I thank, therefore, Sra Dolores Molina González for reminding me that literature is a bit like Simón Bolívar’s eyes in a mirror; Edgardo García for remarking that Australia, like Britain, is an island; and the two Aboriginal women at the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre for the meaning of silence.

Last but not least, I am grateful to The University of Melbourne for offering me the opportunity to study in Australia.

Ilinca Stroe

-

Visions of the Island. The mimetic and the ludic in Australian postcolonialism

Download

ILINCA STROE

Acknowledgments / 7

2022 Foreword / 11

Chapter 1

Inter-sections: (Post)Colonising Mimesis and Ludic Renditions on Antipodean Grounds / 26

1. In Search of Australian Postcolonialism: Unsettled Grounds / 28

2. A Spectrum of Binarism: Recto, Verso, or the Logic of Mimesis / 45

3. In the Ludic Act: Self-Othering Colonial Subjectivity / 71

4. Historical Promotions: Postcolonial Re-visions / 92

Chapter 2

By Means of Holy Ghosts: Modeling Histories in Oscar and Lucinda / 105

1. Founding Fathers, Founding Mothers, and Children Errant / 108

2. Glassy Revisions and Other Appearances: (Con)Figuring Postcolonial Selves / 124

Chapter 3

On the Hero’s Side(s): Composite Annotations in Voss / 142 /

1. Estranged (Con)Texts: Miswriting Rival Histories / 145

2. Reflections on Colonial Tracks: The (Un)Making of a Hero / 167

3. Composing Australia Ludens: “Together is filled with little cells” / 195

Chapter 4

The Reparatory Scales: Figures of Justice in Jack Maggs / 231

1. The Convict Collage: Deluding Misrecognitions / 235

2. Immoral Figures: The “Convict Stain” Complex / 254

3. A Mesmeric Treatment of the “Pathogenic Secret” / 269

4. Comedic Scenery: A Background of Doubleness / 295

Conclusion: Visions of the Island / 328

Bibliography / 332

2022 Foreword / 11

Chapter 1

Inter-sections: (Post)Colonising Mimesis and Ludic Renditions on Antipodean Grounds / 26

1. In Search of Australian Postcolonialism: Unsettled Grounds / 28

2. A Spectrum of Binarism: Recto, Verso, or the Logic of Mimesis / 45

3. In the Ludic Act: Self-Othering Colonial Subjectivity / 71

4. Historical Promotions: Postcolonial Re-visions / 92

Chapter 2

By Means of Holy Ghosts: Modeling Histories in Oscar and Lucinda / 105

1. Founding Fathers, Founding Mothers, and Children Errant / 108

2. Glassy Revisions and Other Appearances: (Con)Figuring Postcolonial Selves / 124

Chapter 3

On the Hero’s Side(s): Composite Annotations in Voss / 142 /

1. Estranged (Con)Texts: Miswriting Rival Histories / 145

2. Reflections on Colonial Tracks: The (Un)Making of a Hero / 167

3. Composing Australia Ludens: “Together is filled with little cells” / 195

Chapter 4

The Reparatory Scales: Figures of Justice in Jack Maggs / 231

1. The Convict Collage: Deluding Misrecognitions / 235

2. Immoral Figures: The “Convict Stain” Complex / 254

3. A Mesmeric Treatment of the “Pathogenic Secret” / 269

4. Comedic Scenery: A Background of Doubleness / 295

Conclusion: Visions of the Island / 328

Bibliography / 332

Visions of the Island: the Mimetic and the Ludic in Australian Postcolonialism is a doctoral thesis based on research conducted by its author between March 1997 and September 2000 as a postgraduate student in the Department of English with Cultural Studies of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne, Australia. Submitted in September 2000, the thesis was examined by Professors Stephen Slemon (University of Alberta) and Alan Lawson (University of Queensland), and the candidate was subsequently awarded the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in October 2001.

The thesis undertakes the task of theorising, on the one hand, a ludic paradigm shift as post-colonial Australia’s response to its colonisation, and identifying, on the other hand, a set of tropes, narrative techniques and devices in three Australian postcolonial novels, as “empirical evidence” of the emergence of that paradigm in contemporary Australian culture. The end goal of the thesis is to propound the ludic postcolonial as a critical reading and hermeneutical method well worth exploring further for its potential to reveal novel ontological and epistemological propositions of present post-colonial cultures.

At the turn of the millennium, however, approaching postcolonial studies required a high degree of awareness of its multifarious sensitivities. While reports of colonial abuse had relegated the view of colonisation as a civilising force to the realm of propagandistic, therefore misleading history made mainly in nineteenth-century Britain, the field of postcolonialism was by no means consensual. Rather, its theorists contributions differed widely around a number of historical, ideological, cultural and political issues.

One of these referred to the legitimacy of the former so-called settler colonies’ claim to postcoloniality at all: of the former colonies of the British Empire, weren’t India and West Africa, which had suffered the full impact of colonial rule, from territory appropriation to the destruction of local cultures and the infringement of individual liberties, more entitled to make postcolonial claims than Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa? And weren’t indigenous Canadians, Australians, etc. a great deal more justified in coordinating postcolonial themes and theories than their non-indigenous, white fellow critics? Finally, in the particular case of Australia, how did its original status as a penal colony of the British Empire – one which started out by literally camping on Aboriginal land regarded as “virgin” territory – relate with and bear on its postcolonial identity?

Chapter I of the thesis, “Inter-sections: (Post)Colo¬nising Mimesis and Ludic Renditions on Antipodean Grounds” sets out to address controversial issues like those summed up above, and position its central argument within the postcolonial theoretical framework.

Three basic concepts instrumental to the argument – namely, Australian postcolonialism, mimesis and the ludic – are discussed here, as well as the argument’s interest in, and investigation of the specific source texts (whether works of fiction, historical accounts or essays) on which the novels analysed draw.

Australian postcolonialism, the first core concept that the thesis uses, has been a highly debated area. In many important theorists’ view, colonisation implied a First World (Britain, Europe) which imposed its rule on a Third World (India, West Africa) regarded as underdeveloped, uncivilised and customarily inhabited by races other than Caucasian/white European.

While these two terms provide the central axis of postcolonial theory – the coloniser/colonised dyad – they leave out what has gradually come to be termed “the Second World”: the colonies where allegedly no social organisation structures were in place prior to the arrival of the colonisers, where the incoming white Caucasians settled the land as agriculturists or graziers, and where colonialism did not end officially with the proclamation of new, totally autonomous and independent states, as in the case of, say, the Republic of India.

Second-World postcolonialism, however, has gradually been accepted within the postcolonial studies field, but with some major differences from Third-World postcolonialism. According to theorist Leela Gandhi, unlike the Third World, which suffered a “full degree” of colonisation, strongly opposes the ideology and practice of colonialism, and endeavours to recuperate at least in part its pre-colonial culture, the Second World experienced only a “half-degree” colonisation, is complicit in the colonialist agenda, and its protagonists, the white settlers, have a pre-eminently ambiguous status as both ideologically colonised by the First World, and oppressive colonisers, themselves, to the indigenous inhabitants of the lands they settled.

Australian postcolonialism belongs to this Second-World framework of postcolonial theory. The cultural, ideological colonisation that “white” Australia suffered resides in the projection, transmission and perpetuation, in the new lands, of a certain mentality, a certain pattern of thought identified later in this chapter as mimetic.

The critique of this pattern, as well as Australian postcolonialism’s other major trait, ambiguity or ambivalence, can be used productively to revisit colonial history, internalise and overcome colonial binaries, trace and explore loci of intersection, of mutual comprehension between the coloniser and the colonised, and dismantle the tenets of the colonial mentality, in a critical process where deconstruction yields reconstruction. This is the Australian postcolonial scope the thesis inhabits.

Mimesis, which is the argument’s second core concept, has been commonly equated with imitation and, in this sense, its function in the colonising enterprise is overt and obvious: to become civilised, organised, educated and prosperous, the colonised necessarily had to copy the manners and habits, the administrative apparatus, instruction methods and business practices of the colonisers. Colonies were required to imitate the colonising “model country,” the end goal of colonisation being, apparently, to clone Britain, to create replicas of it around the Empire.

A tremendously important theorist of mimesis, however, René Girard, maintains that the definition of mimesis as mere imitation is seriously truncated. According to him, mimesis is intrinsically linked to power assertion (a claim which a close reading of Plato’s dialogue Ion, included in this second section, seems to support). It involves two protagonists and a desired object. Initially engaged in fighting over the object, the protagonists gradually drop it from view and end up fighting to annihilate each other. That is because subduing the other, one automatically reinforces him/herself. Hence, self-identification achieved by means of dominating the other is key to mimesis.

Furthermore, an interplay of identity and difference is inherent to mimesis, where the two protagonists, while striving to differ from each other, are essentially identical in their antagonism: fighting, they mirror each other’s gestures, and they both act on exactly the same need to eliminate the other in order to assert him/herself. Thinking of themselves as adversaries, the mimetic protagonists are unknowingly doubles, made identical by their very antagonism. And what appears as the crux of mimesis is the compulsion to define oneself by prevailing over an “other” that must be your opposite - while the realisation of their identity-in-difference is, because perceived as a barrier to the affirmation of “one’s own self,” so intolerable to the mimetic protagonists, that they deny it, push it to the margins of their awareness, keep it unconscious.

Colonisation seems to have taken mimesis from an inter-personal, micro level to a macro one: Edward Said’s archive of Orientalism, for example, illustrates how colonial Britain fashioned itself in opposition to its colonies through a long series of binary opposites (civilised/ primitive, scientific/superstitious, astute/retarded, etc.) - indeed, making of binarism itself a colonising tool.

This polarisation and the subsequent emergence of anti-colonial reversal paradigms in the former colonies, picturing Britain along the corrupt/immoral/backward line, while the now emancipated colonies identified themselves as fair/moral/progressive, indicate that mimesis may well have been the backbone of cultural and ideological colonisation. And that, once its logic and discourse were made, as Leila Gandhi puts it, “strategically available” to the colonised, colonisation can be said to have fulfilled its mission. The cycle was complete: the colonised now defined themselves in the mimetic terms and through the kind of mimetic logic transferred to them by the colonisers.

How does Australia fit in this scheme of colonisation by mimesis? Starting with the 6th century BC, terra australis incognita materialised in the European mind as a “great southern landmass” which counterbalanced the known world of the northern hemisphere (Anaximander of Miletus’s idea), an earthly paradise (in Thomas More’s Utopia, notably at a time when the author’s country was going through serious religious and political turbulences), and a fully rational, perfectly homogenous monoculture (in a few 17th and 18th century European utopias).

Paralleling Said’s Orientalism, a certain kind of “Antipodeanism” can be said to have helped Europe occasionally to define its own identity, whether positively or negatively, in opposition to the Antipodes, so when Britain started colonising terra australis the ground was laid for such mimetic (self-)identifications.

Thus, a late 18th century Britain whose prisons were overflowing with petty criminals and political prisoners was able to re-view itself as righteous and virtuous by sending its delinquent class off to the new penal colony which became its opposite: a place of vice and immorality. Unsurprisingly, in the 1920s there were Australian voices to declare the convicts innocent victims of a morally corrupt imperial Britain.

Such colonial self-identification by opposition and anti-colonial reversed binarisms illustrate that, in Australia’s case, too, mimesis, in its Girardian sense, with its will to opposition, its rejection of similarities and its scapegoating of “the Other” out of a self-assertion need that cannot seem to accept fulfilment by other, non-scapegoating means, transited from the colonisers’ mindset to the worldview of the colonised – completing the cycle of effective colonisation.

The concept of the ludic is approached next. Starting from Johan Huizinga’s now classical monograph on play and recalling the original meaning of the term (ludius meant “stage player” in Latin), the argument focuses on the actor figure. Unlike mimetic protagonists, actors embrace “the Other” intentionally and achieve – in Huizinga’s words – a “conscious oneness of the two” (themselves and the characters they impersonate). So while mimesis denies identity-in-difference, ludic performances do not. The ludic is doubleness assumed.

How does the ludic work in colonial settings? An excellent illustration is provided by Paul Carter, an Australian theorist whose work recovers historically documented colonial encounters which valorise ambi¬valence: in 1519, Hernando Cortés, the Spanish conquistador, and his soldiers reached Mexico. Montezuma, emperor of the Aztecs, asks an envoy to go and inquire what kind of men they were and what they were looking for, and two days later he sends someone to the Spaniards’ camp to “make realistic full-length portraits of Cortés and all his captains….”

After one more week, Montezuma’s official embassy to Cortés enters the Spanish camp. It is led by Quintalbor, “a great Mexican chief who in face, features, and body was very like our Captain. The great Montezuma had chosen him on purpose.” The Spaniards start calling them “‘our Cortés’ and ‘the other Cortés’” (but, symptomatically, not “their Quintalbor” and “our Quintalbor”). They fail to understand the meaning of Montezuma’s choice of a Cortés-like emissary otherwise than as, perhaps, a sign of “weakness”: Montezuma wants to please Cortés. He won’t fight. He is submissive. He is ready to obey.

To a non-mimetic mind, however, Montezuma’s so carefully prepared message may signify quite differently. Regarded as a ludic performance, Quintalbor’s appearance at the head of the emperor’s embassy to the strangers reveals, maybe, not Montezuma’s willingness to be “civilised” or colonised, but his realisation of identity-in-difference. Here are two very different groups of people of distinct races, born thousands of miles away from each other, and yet when they first meet one of the Aztecs looks “very like” one of the Spaniards. Montezuma sees that and he shows it to the strangers, so that they can realise, too. His embassy is an appeal to (shared) awareness.

This example of a colonial encounter, as well as a similar one recounted by Carter and involving the Nyungar Aborigines and Matthew Flinders’s marines on Australian soil, suggest that the postcolonial ludic is very well positioned to: a) unveil the concealed doubleness of mimesis; b) dismantle its power mechanism; and c) reveal potential reconfigurations of the so-called binary opposites by which the colonising mind enforced realities, systems, knowledges.

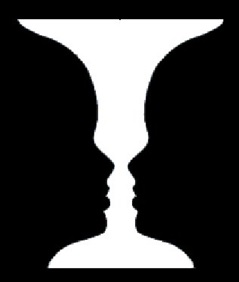

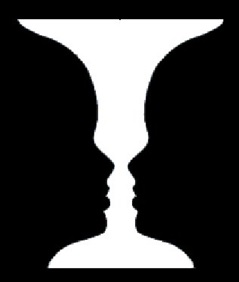

The postcolonial ludic, its working and valences appear summed up in this image:

Conventionally called Rubin’s vase and described as ambiguous bi-stable or reversing two-dimensional, the picture was designed around 1915 by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin to demonstrate that, although it shows two intertwined shapes (the vase, here white, and the two black profiles facing each other) our retina can only retain one shape at a time. The image, Mihai Spariosu maintained, is also illustrative of the co-existence and interdependence of “alternative worlds.”

Within the framework of this argument, the illustration features two “mimetic antagonists”: shape 1 (the white vase) and shape 2 (the black profiles). In order for one to be identified as (meaningful) shape, the other has to be discarded as (meaningless) background. They can only be perceived alternately and by exclusion, even though, as one is background to the other, they actually enable each other.

Watching this illustration in a ludic postcolonial key means becoming aware that we are deeply accustomed to seeing black and white (or any two shapes available to our perception simultaneously) as mutually exclusive; that we usually perceive one by eliminating the other; that the two are in fact interdependent and co-determine each other; and, finally, that mutual exclusion and co-determination can actually be seen to occur at the same time – forcing the limits of our kind of (binary) logic by placing our comprehension faculty at the heart of paradox.

Turning these limitations on their head, the postcolonial ludic attempts to become and stay aware simultaneously of: both black and white, the mutual exclusiveness conditioning, the actual co-determination of the two, as well as the whole that accommodates and enables, in fact, these shapes and this way of shaping. Where does this attempted awareness leave – or take - our common notions of knowledge, power, self, etc.? Searching for the answers accesses an area of possibilities that Montezuma presumably intuited, that the postcolonial ludic ought to explore.

The last section of Chapter I details the kind of engagement with colonial source texts employed by the three Australian postcolonial novels analysed in the thesis. The novels read as – indeed, Peter Carey’s are intended as – “re-historical” fictions, a concept popular with postcolonial theorists because it illustrates concisely the revisionist, transformative approach of postcolonial actors to one of the Empire’s crucial tools: history.

As Slemon explains in “Post-Colonial Allegory and the Transformation of History,” colonial cultures harnessed history to legitimise the “civilising mission” as a necessary step in the unidirectional progress of mankind. Chronicling the one-way advancement of (white) civilisation, however, imperial history obliterated or erased the local histories of the colonised grounds, which thus appeared as “historyless.”

Postcolonial re-historical fictions, which are usually thoroughly researched, add the deleted (hi)stories to the official history record that they engage with. Adjoining “fact” to “fiction,” they make their readers aware not only of the obscured counterparts of, or alternatives to, imperial history, but also the fact that imperial history did customarily work by silencing other histories.

In Slemon’s words, the goal of re-historical postcolonial fictions “is to proceed beyond a ‘determinist view of history’ by revising, reappropriating or reinterpreting history as a concept and, in doing so, to articulate new “codes of recognition” which include “those unrealised intentions … that ‘history’ has rendered silent or invisible….”

In the case of the three novels analysed in the thesis, the retrieved silent histories are the Aborigines’ and the convicts,’ while the colonial source texts they set out to reprocess are all Victorian. Peter Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda draws on Father and Son by Edmund Gosse, who was perceived in the Victorian Age as the father figure of the literary establishment. Patrick White’s Voss is based on the history of explorer Ludwig Leichhardt’s expeditions to inland Australia in the 1840s, but also linked to Carlyle’s Hero worship. And Jack Maggs uses Dickens’s Great Expectations as its primary source, and a network of secondary sources, from convict histories to accounts of public demonstrations of mesmeric practice in Victorian London.

The novelists’ choice of specifically Victorian texts in their re-historical fictions is, as argued in the last section of Chapter I, indicative of their postcolonial commitments, since the Victorian Age was the age of British imperial expansion by excellence. At the time, the home country subjects of Her Majesty were encouraged to think of, and fashion themselves as carriers and as promoters of England, of British values, identity and superiority to the colonies. Even though clumsily - and involuntarily amusingly – this Victorian textbook doggerel illustrates it well:

While boys and girls are learning

To be their empire’s fence

We needn’t really be afraid

Of national decadence.

Therefore Carey’s and White’s revisions of Victorian sources occasion a set of ludic postcolonial propositions vis-à-vis imperial values, thought and power mechanisms at their imperial best.

Chapter II focuses on Oscar and Lucinda by Peter Carey. In the novel, an idealistic young Englishman called Oscar, who comes from a very religious background dominated by his authoritative father, travels to Australia to Christianise Aborigines. He soon falls prey to the corrupt clergy, as well as the local habits of gambling and drinking, and is excommunicated as a consequence.

Nevertheless, he follows his Christianising ideal and joins an expedition party led by a tyrannical explorer to transport and build a glass church in the wilderness. Severely affected by the climate and abused by the expedition leader, he dies inside the church floating down a river. By that point, however, he had met the local Aborigines, connected to them and gained an insight into their own traditions and spirituality.

The chapter outlines the political poetics of the novel. It argues that the Victorian ethos of mimetic authority which the figure of Edmund Gosse (Carey’s source) carries dissolves in the structure of Carey’s narrative technique and in his narrator’s persona, which yield instead postcolonial ludic reconfigurations.

Chapter III analyses Voss by Nobel winner Patrick White. This is the story of a German explorer in mid-nineteenth century Australia, based on real-life explorer Ludwig Leichhardt. Voss organises an expedition party to travel towards and map the unknown interior of the country, and his project is financed by the rich local establishment, who expect him to find fertile farming land.

As Voss and his group progress inland, they enter Aboriginal territory and encounter its otherness through at times extreme spiritual experiences. The party also suffer from hunger, cold and other deprivations, and Voss is eventually captured and beheaded by the Aborigines as part of a ritual – leaving behind a bewildered group of sponsors and supporters who are unlikely to ever find out the real (hi)story.

The chapter examines White’s engagement with two rival histories of the expedition, Leichhardt’s Journal and Alec Chisholm’s Strange New World, which can be read as “mimetic antagonists,” and finds that devices such as pluri-contextualisation and inter-characterisation undermine and reconfigure the initial mimetic scheme.

Chapter IV discusses Carey’s Jack Maggs, often read as the “reverse story” of Charles Dickens’s Magwitch in Great Expectations. In the Australian novel, the ex-convict returns to England illegally to find the young gentleman he “made” and paid for, Phipps (Dickens’s Pip). There he starts being psychologically explored and exploited by a young, ambitious writer (Dickens’s alias) who practices mesmerism on him.

During a mesmeric session Maggs’s secret is revealed and those who find out that he is a former convict of the Crown threaten to turn him over to the authorities. Helped by a young maid called Mercy, however, Maggs manages to escape back to Australia with her, renounces his dream of “owning a gentleman” back “home” in England, and becomes reconciled with his Australian identity, life and commitments.

The chapter attempts to go beyond the mere reversal paradigm and to demonstrate that Jack Maggs is not simply an anti-colonial text showing Dickens, not the convict, to be the morally corrupt character, but a proposition to analyse and revise the mimetic justice mechanism which generated the lasting “convict stain” in the Australian colonial psyche.

In the Conclusion of this thesis, the argument equates the ludic postcolonial vision with diplomacy (etymologically, “double vision”): with doubleness assumed. And, in this sense, its political poetics promises to deliver a Second-World potential for enhanced under¬standing, renewed knowledge and mutual reshaping.

The thesis undertakes the task of theorising, on the one hand, a ludic paradigm shift as post-colonial Australia’s response to its colonisation, and identifying, on the other hand, a set of tropes, narrative techniques and devices in three Australian postcolonial novels, as “empirical evidence” of the emergence of that paradigm in contemporary Australian culture. The end goal of the thesis is to propound the ludic postcolonial as a critical reading and hermeneutical method well worth exploring further for its potential to reveal novel ontological and epistemological propositions of present post-colonial cultures.

At the turn of the millennium, however, approaching postcolonial studies required a high degree of awareness of its multifarious sensitivities. While reports of colonial abuse had relegated the view of colonisation as a civilising force to the realm of propagandistic, therefore misleading history made mainly in nineteenth-century Britain, the field of postcolonialism was by no means consensual. Rather, its theorists contributions differed widely around a number of historical, ideological, cultural and political issues.

One of these referred to the legitimacy of the former so-called settler colonies’ claim to postcoloniality at all: of the former colonies of the British Empire, weren’t India and West Africa, which had suffered the full impact of colonial rule, from territory appropriation to the destruction of local cultures and the infringement of individual liberties, more entitled to make postcolonial claims than Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa? And weren’t indigenous Canadians, Australians, etc. a great deal more justified in coordinating postcolonial themes and theories than their non-indigenous, white fellow critics? Finally, in the particular case of Australia, how did its original status as a penal colony of the British Empire – one which started out by literally camping on Aboriginal land regarded as “virgin” territory – relate with and bear on its postcolonial identity?

Chapter I of the thesis, “Inter-sections: (Post)Colo¬nising Mimesis and Ludic Renditions on Antipodean Grounds” sets out to address controversial issues like those summed up above, and position its central argument within the postcolonial theoretical framework.

Three basic concepts instrumental to the argument – namely, Australian postcolonialism, mimesis and the ludic – are discussed here, as well as the argument’s interest in, and investigation of the specific source texts (whether works of fiction, historical accounts or essays) on which the novels analysed draw.

Australian postcolonialism, the first core concept that the thesis uses, has been a highly debated area. In many important theorists’ view, colonisation implied a First World (Britain, Europe) which imposed its rule on a Third World (India, West Africa) regarded as underdeveloped, uncivilised and customarily inhabited by races other than Caucasian/white European.

While these two terms provide the central axis of postcolonial theory – the coloniser/colonised dyad – they leave out what has gradually come to be termed “the Second World”: the colonies where allegedly no social organisation structures were in place prior to the arrival of the colonisers, where the incoming white Caucasians settled the land as agriculturists or graziers, and where colonialism did not end officially with the proclamation of new, totally autonomous and independent states, as in the case of, say, the Republic of India.

Second-World postcolonialism, however, has gradually been accepted within the postcolonial studies field, but with some major differences from Third-World postcolonialism. According to theorist Leela Gandhi, unlike the Third World, which suffered a “full degree” of colonisation, strongly opposes the ideology and practice of colonialism, and endeavours to recuperate at least in part its pre-colonial culture, the Second World experienced only a “half-degree” colonisation, is complicit in the colonialist agenda, and its protagonists, the white settlers, have a pre-eminently ambiguous status as both ideologically colonised by the First World, and oppressive colonisers, themselves, to the indigenous inhabitants of the lands they settled.

Australian postcolonialism belongs to this Second-World framework of postcolonial theory. The cultural, ideological colonisation that “white” Australia suffered resides in the projection, transmission and perpetuation, in the new lands, of a certain mentality, a certain pattern of thought identified later in this chapter as mimetic.

The critique of this pattern, as well as Australian postcolonialism’s other major trait, ambiguity or ambivalence, can be used productively to revisit colonial history, internalise and overcome colonial binaries, trace and explore loci of intersection, of mutual comprehension between the coloniser and the colonised, and dismantle the tenets of the colonial mentality, in a critical process where deconstruction yields reconstruction. This is the Australian postcolonial scope the thesis inhabits.

Mimesis, which is the argument’s second core concept, has been commonly equated with imitation and, in this sense, its function in the colonising enterprise is overt and obvious: to become civilised, organised, educated and prosperous, the colonised necessarily had to copy the manners and habits, the administrative apparatus, instruction methods and business practices of the colonisers. Colonies were required to imitate the colonising “model country,” the end goal of colonisation being, apparently, to clone Britain, to create replicas of it around the Empire.

A tremendously important theorist of mimesis, however, René Girard, maintains that the definition of mimesis as mere imitation is seriously truncated. According to him, mimesis is intrinsically linked to power assertion (a claim which a close reading of Plato’s dialogue Ion, included in this second section, seems to support). It involves two protagonists and a desired object. Initially engaged in fighting over the object, the protagonists gradually drop it from view and end up fighting to annihilate each other. That is because subduing the other, one automatically reinforces him/herself. Hence, self-identification achieved by means of dominating the other is key to mimesis.

Furthermore, an interplay of identity and difference is inherent to mimesis, where the two protagonists, while striving to differ from each other, are essentially identical in their antagonism: fighting, they mirror each other’s gestures, and they both act on exactly the same need to eliminate the other in order to assert him/herself. Thinking of themselves as adversaries, the mimetic protagonists are unknowingly doubles, made identical by their very antagonism. And what appears as the crux of mimesis is the compulsion to define oneself by prevailing over an “other” that must be your opposite - while the realisation of their identity-in-difference is, because perceived as a barrier to the affirmation of “one’s own self,” so intolerable to the mimetic protagonists, that they deny it, push it to the margins of their awareness, keep it unconscious.

Colonisation seems to have taken mimesis from an inter-personal, micro level to a macro one: Edward Said’s archive of Orientalism, for example, illustrates how colonial Britain fashioned itself in opposition to its colonies through a long series of binary opposites (civilised/ primitive, scientific/superstitious, astute/retarded, etc.) - indeed, making of binarism itself a colonising tool.

This polarisation and the subsequent emergence of anti-colonial reversal paradigms in the former colonies, picturing Britain along the corrupt/immoral/backward line, while the now emancipated colonies identified themselves as fair/moral/progressive, indicate that mimesis may well have been the backbone of cultural and ideological colonisation. And that, once its logic and discourse were made, as Leila Gandhi puts it, “strategically available” to the colonised, colonisation can be said to have fulfilled its mission. The cycle was complete: the colonised now defined themselves in the mimetic terms and through the kind of mimetic logic transferred to them by the colonisers.

How does Australia fit in this scheme of colonisation by mimesis? Starting with the 6th century BC, terra australis incognita materialised in the European mind as a “great southern landmass” which counterbalanced the known world of the northern hemisphere (Anaximander of Miletus’s idea), an earthly paradise (in Thomas More’s Utopia, notably at a time when the author’s country was going through serious religious and political turbulences), and a fully rational, perfectly homogenous monoculture (in a few 17th and 18th century European utopias).

Paralleling Said’s Orientalism, a certain kind of “Antipodeanism” can be said to have helped Europe occasionally to define its own identity, whether positively or negatively, in opposition to the Antipodes, so when Britain started colonising terra australis the ground was laid for such mimetic (self-)identifications.

Thus, a late 18th century Britain whose prisons were overflowing with petty criminals and political prisoners was able to re-view itself as righteous and virtuous by sending its delinquent class off to the new penal colony which became its opposite: a place of vice and immorality. Unsurprisingly, in the 1920s there were Australian voices to declare the convicts innocent victims of a morally corrupt imperial Britain.

Such colonial self-identification by opposition and anti-colonial reversed binarisms illustrate that, in Australia’s case, too, mimesis, in its Girardian sense, with its will to opposition, its rejection of similarities and its scapegoating of “the Other” out of a self-assertion need that cannot seem to accept fulfilment by other, non-scapegoating means, transited from the colonisers’ mindset to the worldview of the colonised – completing the cycle of effective colonisation.

The concept of the ludic is approached next. Starting from Johan Huizinga’s now classical monograph on play and recalling the original meaning of the term (ludius meant “stage player” in Latin), the argument focuses on the actor figure. Unlike mimetic protagonists, actors embrace “the Other” intentionally and achieve – in Huizinga’s words – a “conscious oneness of the two” (themselves and the characters they impersonate). So while mimesis denies identity-in-difference, ludic performances do not. The ludic is doubleness assumed.

How does the ludic work in colonial settings? An excellent illustration is provided by Paul Carter, an Australian theorist whose work recovers historically documented colonial encounters which valorise ambi¬valence: in 1519, Hernando Cortés, the Spanish conquistador, and his soldiers reached Mexico. Montezuma, emperor of the Aztecs, asks an envoy to go and inquire what kind of men they were and what they were looking for, and two days later he sends someone to the Spaniards’ camp to “make realistic full-length portraits of Cortés and all his captains….”

After one more week, Montezuma’s official embassy to Cortés enters the Spanish camp. It is led by Quintalbor, “a great Mexican chief who in face, features, and body was very like our Captain. The great Montezuma had chosen him on purpose.” The Spaniards start calling them “‘our Cortés’ and ‘the other Cortés’” (but, symptomatically, not “their Quintalbor” and “our Quintalbor”). They fail to understand the meaning of Montezuma’s choice of a Cortés-like emissary otherwise than as, perhaps, a sign of “weakness”: Montezuma wants to please Cortés. He won’t fight. He is submissive. He is ready to obey.

To a non-mimetic mind, however, Montezuma’s so carefully prepared message may signify quite differently. Regarded as a ludic performance, Quintalbor’s appearance at the head of the emperor’s embassy to the strangers reveals, maybe, not Montezuma’s willingness to be “civilised” or colonised, but his realisation of identity-in-difference. Here are two very different groups of people of distinct races, born thousands of miles away from each other, and yet when they first meet one of the Aztecs looks “very like” one of the Spaniards. Montezuma sees that and he shows it to the strangers, so that they can realise, too. His embassy is an appeal to (shared) awareness.

This example of a colonial encounter, as well as a similar one recounted by Carter and involving the Nyungar Aborigines and Matthew Flinders’s marines on Australian soil, suggest that the postcolonial ludic is very well positioned to: a) unveil the concealed doubleness of mimesis; b) dismantle its power mechanism; and c) reveal potential reconfigurations of the so-called binary opposites by which the colonising mind enforced realities, systems, knowledges.

The postcolonial ludic, its working and valences appear summed up in this image:

Conventionally called Rubin’s vase and described as ambiguous bi-stable or reversing two-dimensional, the picture was designed around 1915 by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin to demonstrate that, although it shows two intertwined shapes (the vase, here white, and the two black profiles facing each other) our retina can only retain one shape at a time. The image, Mihai Spariosu maintained, is also illustrative of the co-existence and interdependence of “alternative worlds.”

Within the framework of this argument, the illustration features two “mimetic antagonists”: shape 1 (the white vase) and shape 2 (the black profiles). In order for one to be identified as (meaningful) shape, the other has to be discarded as (meaningless) background. They can only be perceived alternately and by exclusion, even though, as one is background to the other, they actually enable each other.

Watching this illustration in a ludic postcolonial key means becoming aware that we are deeply accustomed to seeing black and white (or any two shapes available to our perception simultaneously) as mutually exclusive; that we usually perceive one by eliminating the other; that the two are in fact interdependent and co-determine each other; and, finally, that mutual exclusion and co-determination can actually be seen to occur at the same time – forcing the limits of our kind of (binary) logic by placing our comprehension faculty at the heart of paradox.

Turning these limitations on their head, the postcolonial ludic attempts to become and stay aware simultaneously of: both black and white, the mutual exclusiveness conditioning, the actual co-determination of the two, as well as the whole that accommodates and enables, in fact, these shapes and this way of shaping. Where does this attempted awareness leave – or take - our common notions of knowledge, power, self, etc.? Searching for the answers accesses an area of possibilities that Montezuma presumably intuited, that the postcolonial ludic ought to explore.

The last section of Chapter I details the kind of engagement with colonial source texts employed by the three Australian postcolonial novels analysed in the thesis. The novels read as – indeed, Peter Carey’s are intended as – “re-historical” fictions, a concept popular with postcolonial theorists because it illustrates concisely the revisionist, transformative approach of postcolonial actors to one of the Empire’s crucial tools: history.

As Slemon explains in “Post-Colonial Allegory and the Transformation of History,” colonial cultures harnessed history to legitimise the “civilising mission” as a necessary step in the unidirectional progress of mankind. Chronicling the one-way advancement of (white) civilisation, however, imperial history obliterated or erased the local histories of the colonised grounds, which thus appeared as “historyless.”

Postcolonial re-historical fictions, which are usually thoroughly researched, add the deleted (hi)stories to the official history record that they engage with. Adjoining “fact” to “fiction,” they make their readers aware not only of the obscured counterparts of, or alternatives to, imperial history, but also the fact that imperial history did customarily work by silencing other histories.

In Slemon’s words, the goal of re-historical postcolonial fictions “is to proceed beyond a ‘determinist view of history’ by revising, reappropriating or reinterpreting history as a concept and, in doing so, to articulate new “codes of recognition” which include “those unrealised intentions … that ‘history’ has rendered silent or invisible….”

In the case of the three novels analysed in the thesis, the retrieved silent histories are the Aborigines’ and the convicts,’ while the colonial source texts they set out to reprocess are all Victorian. Peter Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda draws on Father and Son by Edmund Gosse, who was perceived in the Victorian Age as the father figure of the literary establishment. Patrick White’s Voss is based on the history of explorer Ludwig Leichhardt’s expeditions to inland Australia in the 1840s, but also linked to Carlyle’s Hero worship. And Jack Maggs uses Dickens’s Great Expectations as its primary source, and a network of secondary sources, from convict histories to accounts of public demonstrations of mesmeric practice in Victorian London.

The novelists’ choice of specifically Victorian texts in their re-historical fictions is, as argued in the last section of Chapter I, indicative of their postcolonial commitments, since the Victorian Age was the age of British imperial expansion by excellence. At the time, the home country subjects of Her Majesty were encouraged to think of, and fashion themselves as carriers and as promoters of England, of British values, identity and superiority to the colonies. Even though clumsily - and involuntarily amusingly – this Victorian textbook doggerel illustrates it well:

While boys and girls are learning

To be their empire’s fence

We needn’t really be afraid

Of national decadence.

Therefore Carey’s and White’s revisions of Victorian sources occasion a set of ludic postcolonial propositions vis-à-vis imperial values, thought and power mechanisms at their imperial best.

Chapter II focuses on Oscar and Lucinda by Peter Carey. In the novel, an idealistic young Englishman called Oscar, who comes from a very religious background dominated by his authoritative father, travels to Australia to Christianise Aborigines. He soon falls prey to the corrupt clergy, as well as the local habits of gambling and drinking, and is excommunicated as a consequence.

Nevertheless, he follows his Christianising ideal and joins an expedition party led by a tyrannical explorer to transport and build a glass church in the wilderness. Severely affected by the climate and abused by the expedition leader, he dies inside the church floating down a river. By that point, however, he had met the local Aborigines, connected to them and gained an insight into their own traditions and spirituality.

The chapter outlines the political poetics of the novel. It argues that the Victorian ethos of mimetic authority which the figure of Edmund Gosse (Carey’s source) carries dissolves in the structure of Carey’s narrative technique and in his narrator’s persona, which yield instead postcolonial ludic reconfigurations.

Chapter III analyses Voss by Nobel winner Patrick White. This is the story of a German explorer in mid-nineteenth century Australia, based on real-life explorer Ludwig Leichhardt. Voss organises an expedition party to travel towards and map the unknown interior of the country, and his project is financed by the rich local establishment, who expect him to find fertile farming land.

As Voss and his group progress inland, they enter Aboriginal territory and encounter its otherness through at times extreme spiritual experiences. The party also suffer from hunger, cold and other deprivations, and Voss is eventually captured and beheaded by the Aborigines as part of a ritual – leaving behind a bewildered group of sponsors and supporters who are unlikely to ever find out the real (hi)story.

The chapter examines White’s engagement with two rival histories of the expedition, Leichhardt’s Journal and Alec Chisholm’s Strange New World, which can be read as “mimetic antagonists,” and finds that devices such as pluri-contextualisation and inter-characterisation undermine and reconfigure the initial mimetic scheme.

Chapter IV discusses Carey’s Jack Maggs, often read as the “reverse story” of Charles Dickens’s Magwitch in Great Expectations. In the Australian novel, the ex-convict returns to England illegally to find the young gentleman he “made” and paid for, Phipps (Dickens’s Pip). There he starts being psychologically explored and exploited by a young, ambitious writer (Dickens’s alias) who practices mesmerism on him.

During a mesmeric session Maggs’s secret is revealed and those who find out that he is a former convict of the Crown threaten to turn him over to the authorities. Helped by a young maid called Mercy, however, Maggs manages to escape back to Australia with her, renounces his dream of “owning a gentleman” back “home” in England, and becomes reconciled with his Australian identity, life and commitments.

The chapter attempts to go beyond the mere reversal paradigm and to demonstrate that Jack Maggs is not simply an anti-colonial text showing Dickens, not the convict, to be the morally corrupt character, but a proposition to analyse and revise the mimetic justice mechanism which generated the lasting “convict stain” in the Australian colonial psyche.

In the Conclusion of this thesis, the argument equates the ludic postcolonial vision with diplomacy (etymologically, “double vision”): with doubleness assumed. And, in this sense, its political poetics promises to deliver a Second-World potential for enhanced under¬standing, renewed knowledge and mutual reshaping.

If you want to express your opinion about this product you can add a review.

write a review

Customer Support Monday - Friday, between 8.00 - 16.00

0745 200 718 0745 200 357 comenzi@editurauniversitara.ro

6359.png)

![Visions of the Island. The mimetic and the ludic in Australian postcolonialism - Ilinca Stroe [1] Visions of the Island. The mimetic and the ludic in Australian postcolonialism - Ilinca Stroe [1]](https://gomagcdn.ro/domains/editurauniversitara.ro/files/product/large/161039.jpg)